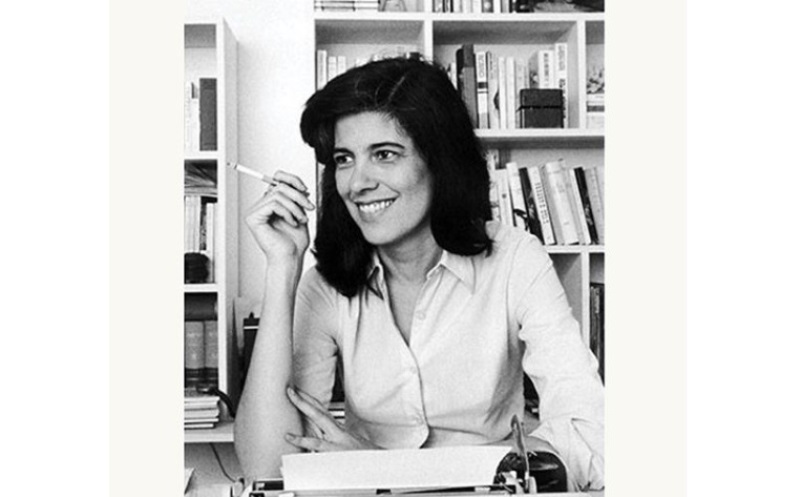

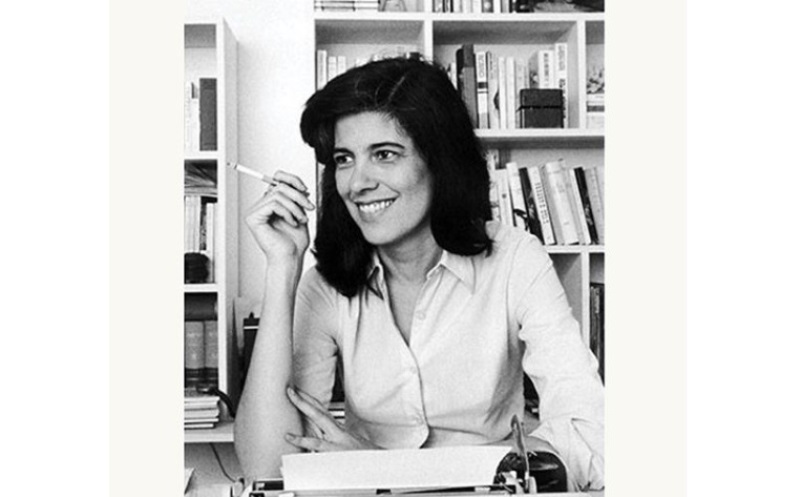

The Dark Lady Of American Letters, Susan Sontag, was born Susan Rosenblatt, in New York City, on January 16, 1933. Her talents are multitudinous in nature, and she has worked as a writer, philosopher, filmmaker, photographer, activist, among other things. Sontag began and ended her writing career with fiction, but in between she wrote several controversial essays and treatises, focusing on subjects like photography, the AIDS epidemic, historical accounts, war and art.

Featured image source: Instagram

Her parents, Mildred and Jack Rosenblatt, were both Jews of Lithuanian and Polish descent. Sontag’s father was a fur trader in China, and died of tuberculosis in 1939, when she was only five years old. Seven years later, her mother married a US Army Captain, named Nathan Sontag. Susan and her sister adopted their step father’s last name, even though he never officially adopted them. Sontag and her family moved around the country quite a bit. From New York City, she and her family traveled to Tucson, Arizona and then to California.

Suggested read: A Tribute To Mary Oliver The Poet Who Taught Us To Be Curious

She has often described her childhood as lonely and miserable, with a cold and distant mother making things worse for the young Sontag. Like most troubled children with an affinity for staying away from people, she found refuge in the company of books. As a child, she greatly enjoyed the literary works of Dickens, Poe and Shakespeare; this is proof of her maturity at such a tender age. Her love for books, in fact, continued to accompany her throughout the course of her fruitful life. Her thirst for knowledge was never quite satiated, and she was always pushing herself to go further ahead. In a 1995 interview with Edward Hirsch for The Paris Review, Sontag admitted, “I got through my childhood in a delirium of literary exaltations.”

The apartment in Manhattan where she lived, is said to have been home to more than fifteen thousand books, each with sheets of paper stuffed in between pages, scribbled with notes on what she has read so far, and notes on further reading that was supposed to be done. Her collection includes books on art and architecture, history, medicine, theatre and dance, philosophy and psychology, religion, photography, opera and a plethora of other interesting subjects, which would take one an entire lifetime to finish reading. She was also the proud owner of several volumes of European literature, ranging from French, Spanish, German, and Italian. Sontag also had a vast collection of Japanese literature; along with British and American literature which began all the way from Beowulf. She is also known to have meticulously arranged every single one of her books in perfect chronological order.

Sontag has written extensively about war and its effects, as well as about war photography and how it moulds our perceptions of war atrocities, and formation of empathy in our minds, by falsifying images or desensitizing us to the horrors of war. She understood war very early on in her life, her father died at the time of the Japanese invasion of China. She remembers hearing about the First World War in elementary school. In that very classroom was her best friend, a Spanish civil war refugee. In her literary piece on Roland Barthes, Sontag expressed her surprise at the fact that he had mentioned the word war not even once throughout his writing, despite having suffered in some way in both the World Wars. She once wrote,

“My subject is war, and anything about any war that does not show the appalling concreteness of destruction and death is a dangerous lie.”

Suggested read: Ruby Eliot Who Transforms Real Life Struggle Into Giggles!

In Regarding The Pain Of Others, Sontag scrutinizes the destructive nature of war by turning her gaze on war photography and its contributions to creating generations of men and women, who view these images in a certain isolation from the world around them and with a complete lack of empathy. These images are viewed less as reminders of the horrifying scourge of war and more as reminders that “at least it’s not happening to us”. Moreover, with the continuous dumping of images and a constant supply of visual stimuli, the problem of moral oversaturation is a very real phenomenon in the modern world. After a point, we fail to see the images of bloodied children, houses reduced to rubble, death and destruction as anything more than mere images. This is where the desensitisation of the effects of war begins to take shape in our collective consciousness. A society devoid of empathy is one which has no humanity left in it. This book tries to solve this very problem of distance between us and the pain of others. She warns us of this moral stagnation where images of atrocities do not evoke sympathy, and instead this onslaught of images makes us apathetic and passive. Sontag is alerting us to not fall prey to the collective amnesia that plagues modern society.

Diseases, especially those that are epidemic, are not merely biological phenomenon. How a society responds to such diseases sheds light on the social, cultural and moral values of a society, and also reflects its attitude towards death, fear, illness, disability, etc. How we perceive diseases, and intervene during their outbreak are largely determined by social norms and political force. In this regard, diseases are socially constructed. Susan Sontag’s Illness As Metaphor, first published in the New York Review Of Books in 1978, is perhaps the most widely read and provocative modern treatises on the social aspect of diseases. She writes-

“My point is that illness is not a metaphor, and that the most truthful way of regarding illness- and the healthiest way of being ill- is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.”

According to Sontag, metaphors for illnesses tend to have deep, negative connotations which make the victims feel alienated and stigmatized by society. As a society, we usually have a reductive approach to complex diseases which are not nearly the evil, invincible predator that we perceive them to be. In AIDS And Its Metaphors, Sontag extends her argument towards sexually transmitted infections as well. She opined that the way we talk and think about the disease makes it appear a lot more deadly than it already is. However, her critics have logically refuted most of the arguments she makes in this particular piece by arguing that the metaphors accorded to AIDS are appropriate, and do not amount to misrepresentation. Considering the deadly nature of the disease, a fatalistic view of AIDS does not seem to be too out of line.

The most cited, popular and controversial work by Susan Sontag is undoubtedly her series of essays On Photography, originally appearing in The New York Review Of Books between 1973 and 1977. She underscores the shift in the politics of photography in the modern era since it was first was first invented. She writes how photography’s purpose has been an ever evolving one. “In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe. They are a grammar, and, even more importantly, an ethics of seeing. Finally, the most grandiose result of the photographic enterprise is to give us the sense that we can hold the whole world in our heads- as an anthology of images,” Sontag wrote in one of the essays from this series titled In Plato’s Cave.

She writes about the capacity of photographs to incriminate, furnish evidence, and the tendency of photographers to exercise their authority over how a photograph is supposed to look; what is to be captured and what is to be left out in a photograph depends on the ideological leanings as well aesthetic sensibilities of the photographer. Photographs are thus, as interpretive as any other art form. They are a “portrait chronicle” that every family in the modern society religiously maintains. It is their tool for memorialisation of the family life and a connection to the past. Photography is also inextricably linked with tourism. She writes-

“It seems positively unnatural to travel for pleasure without taking a camera along. Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had. Photographs document sequences of consumption carried on outside the view of family, friends and neighbors.”

Suggested read: Take Your Broken Heart, Turn It Into Art: Here’s Mari Andrew Doing Just That

Sontag elucidates how photography is an act of non-intervention. The reason we have such chilling photographic evidences of some of the most horrifying events is because the photographer chose to click a picture rather than intervening in the action. This resonates with the state of our society today, wherein people actually choose to remain a bystander and take a picture rather than helping out the victims in front of them.

Sontag has worked on and written about a multitude of subjects, as is evident from the above discussion on some of her most notable works. She has contributed to various subjects, and remains one of the greatest modern intellectuals that the USA can boast of producing.

Featured image source: Instagram