What constitutes a poem or a song? They are both based on rhythmic patterns, lyric structures, and forms of expression. In the postmodern narrative, literature is no longer restricted to heavy books or traditionally approved poetry. Literature is now free-flowing, all inclusive, and very welcoming of anything that has an idea to present. On this World Poetry Day, we are here to celebrate the demolishing of elitist discrimination.

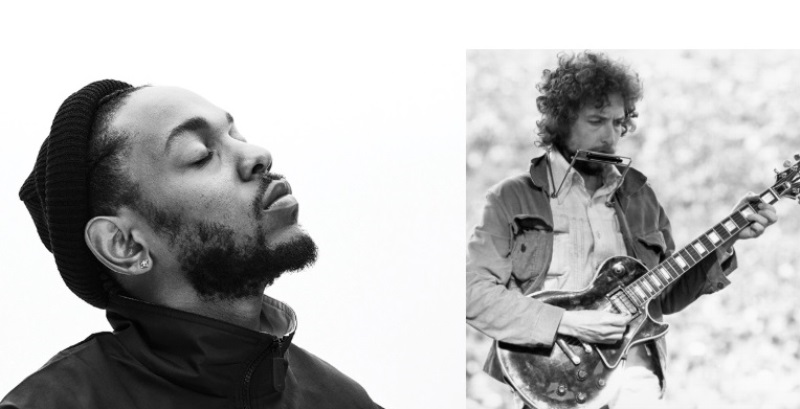

For ages, the highbrow gatekeepers of literary sects have sealed genres of texts into air-tight compartments. There has been a certain misplaced sense of pride in not listening to new-age pop, or in having read a plethora of unnecessary, confusing, big-worded novels. That school of thought has ebbed ever so slightly since Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize for Literature (2016), and Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer Prize (2018), but the debate is still raging fiercely.

Suggested read: Sometimes Life Seems Tough, That’s Where Poetry Steps In

A few months ago, a friend asked me whether song lyrics and poetry could be considered under the same wing or not. Staring at the Sufjan Stevens song list that had been playing on loop, I said, “yes”. The idea that poetry is superior or that music is less intense or less complex is an outdated thought. It is also an uneducated presumption that songs have less interpretive credit than poems do. Music is extensively layered too. If a poem has myriad ways of being viewed, then so does a song. Hozier’s, ‘Take Me to Church’, sounds like an ode to love and sexual liberty, but the official music video interprets it in the light of homosexual oppression. His song ‘Cherry Wine’ sounds like a mellifluous lullaby for a loved one, but the official music video interprets it as a warning for domestic abuse and Stockholm syndrome. This World Poetry Day, we try to explore how music cannot be unjustifiably separated from great literary canons; how songs qualify as poetry.

To me, Sufjan’s lyrics to ‘Fourth of July’,

“The evil, it spread like a fever ahead

It was night when you died, my firefly

What could I have said to raise you from the dead?

Oh, could I be the sky on the Fourth of July?

‘Well, you do enough talk

My little hawk, why do you cry?

Tell me, what did you learn from the Tillamook burn?

Or the Fourth of July?

We’re all gonna die.’”

can be contrasted to Emily Dickinson’s, ‘Because I Could Not Wait For Death’:

“Since then – ‘tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the

Day I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity”

or Dylan Thomas’, ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night”:

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

The former makes peace with the idea of isolation, of fading away into another realm, of the inevitability of death being a part of the cycle of life. The latter expresses anguish for the dying light of the listener (possibly Thomas’ father), urging him to triumph over oblivion. Sufjan’s lyrics- intended as an exchange between a son and his dying mother, as in his real life- reflect the same essence.

A WordPress blog titled ‘The Plantonist’ writes,

“In the ancient world, and in the middle ages, poetry was usually accompanied by music. The Greeks had their lyre, and the medievals had their ballads. Poetry without music was seen as artificial. The troubadour poetry may well have been sung as well. Dante and Petrarch copied the Roman stanzas that they found in old books, and invented the notion that poetry could be purely intellectual and rhythmic in itself. And this is a fine thing; clearly, many people since their time have found certain lyrics to be very potent and powerful by themselves, without recourse to musical accompaniment. In some cases, one could argue that any music would only draw away from the many levels of meaning and sound that can be savored when one is allowed to concentrate solely on the lyrics.”

Suggested read: Odes That Will Fill You With Love For Poetry

Two opposing schools of thought believe that lyrics can and should be appreciated in isolation, while the other asserts that music enhances and delivers the true nature of the lyrical component. Taking this into consideration, the twenty-first century’s advent of Performance Poetry or the Spoken Word art form is testament to the ability of poetry to be taken off paper. While previously, the argument against song lyrics included its lack of proper stanzaic patterns, and/or scansion, the Spoken Word did away with all those restrictions, elevating poetry to a modern, ‘stream of consciousness’-like, unfettered narrative. Phil Kaye’s ‘Repetition’ reads beautifully on paper, but the poignancy is conveyed far more intensely when one watches him perform the piece. Patrick Roche’s, ‘Siri: A Coping Mechanism’, is a brilliant example of modernist poetry. But its enactment adds a certain element to it, without taking away its self-sufficiency as a piece of poem. The development of audiobooks, the popularity of Benedict Cumberbatch’s voice in BBC’s narrations, has hardly taken anything away from novels. One cannot argue that the audiobook does not qualify as literature, or that the presence of perceivable sounds (like horses’ hooves, rain pattering, horns blaring) to aid the narrative, take away from the focus that is due to the story at hand. Why then do we readily mete out this approach to songs? On this World Poetry Day, we should take a step forward against bias and prejudice in the domain of art.

An article published in The New Republic says,

“The anti-Rockists or ‘poptimists’ emphasized instead that performance, charisma, persona, sex appeal, and rhythm should all be considered at least as important as expressive language.”

When we read a piece of poetry in our mind, our narration varies from that of another. Literature, in itself, is personal. It is not a passive intake, a passive dumping of words or scenarios. One partakes and participates in the text at hand, in order to obtain the ultimate experience of it. So,

“The awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Bob Dylan (in 2016) therefore produced a moment of ambivalence for many fans committed to the principle that pop must never be treated as primarily verbal.”

Adam Bradley’s, ‘The Poetry of Pop’ scans Taylor Swift’s song, ‘Bad Blood’. It lays out Swift’s metrical basis for the song, the syllable count, and the basic structure on which the rhythm of the song has been built. However, Ivan Krielkamp rightfully examines:

“An extended close reading of the metrical variations of a Taylor Swift recording can seem, at first blush, like the most wrong-headed form of pop criticism imaginable: one that isolates the song’s language, abstracting it not only from music but from vocal expression, and that privileges the (surely fairly unremarkable?) words of the song at the expense of everything that actually makes us want to hear it more than once. Who listens to Taylor Swift for the syllable count?”

In The Washington Post, Michael Lindgren writes,

“He (Adam Bradley) denies the need for ‘creating a canon of pop lyrics, so that Steven Tyler can sit with Shakespeare,’ instead proposing a superb formulation: ‘Pop,’ he writes, ‘is a poetry whose success lies in getting you to forget that it is poetry at all.’”

Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer Prize in 2018 for his album, ‘DAMN.’, not only put hip hop on the prominent chart, but also gave it the status it has deserved for a long time. Brain Wheeler writes for BBC,

“In 2003, no less a figure than Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney hailed ‘this guy Eminem’, who he said had ‘created a sense of what is possible’ and ‘sent a voltage around his generation’.”

The repetition, the pauses, the incoherence, the lack of linear progression- all of this has been held against hip hop by the traditional school of literary thought. However, the ‘dashes’ (pauses) can be traced back to Emily Dickinson’s hailed, ‘It’s Easy to Invent a Life’, and several other poems. The work that is not intended or tailored towards publication, will reveal our true selves. We witness the very same in the ‘stream of consciousness’-like recording of Dickinson’s thoughts in her hailed poetry. Fragmentation is an essential part of postmodern poetry, easily visible in the works of Allen Ginsberg. Why then should we criticize something in hip hop while hailing the same in published poetry that passes orthodox traditional gatekeeping?

Matthew Zapruder writes for the Boston Review,

“Many musical artists present their song lyrics as poetry. This reflects not a commercial move on their part, but a desire for the words they write to be taken seriously. It is certainly true that poems are taught (for better or worse) in classrooms and made a part of the canon of literature, whereas songs, especially popular ones, usually are not. If song lyrics are studied in school, often it is ethnographically or anthropologically, to learn something about a culture, not as literature per se. What I suppose some musicians want is not to be considered poets, but for their lyrics to be read with the same respect they imagine poems are.”

Suggested read: “We Have Pain On Earth” Naomi Shihab Nye And Her Magnificent Poetry

Is it possible that the true essence of poetry has always lied in its performance, as always claimed about drama? Or, do all performances, including songs, need to be read as literary texts for their essence to be understood?

Featured image source: Instagram