“I like to get people from my neighborhood, someone that’s fresh out of prison for five years, and see their faces when they go to New York, when they go out of the country. Shit, that’s fun for me. You see it through their eyes and you see ’em light up.”

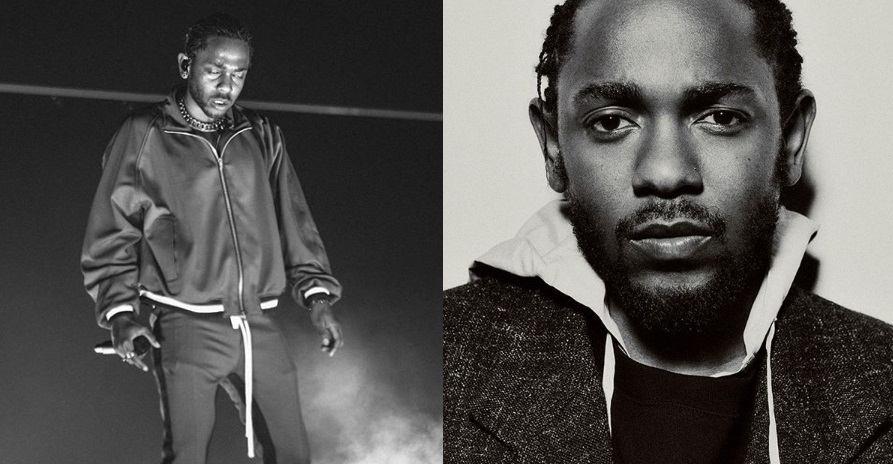

Kendrick Lamar is a hero. This century has had the fortune of being blessed with a plethora of hip-hop artists. What makes Lamar stand apart, and genuinely worthy of the Pulitzer, is his superpower. Some would attribute that power to his music. One cannot help but speak highly about the genius of his songs’ synthesis. Some would argue that his music videos are par excellence. It is undeniable that the quality and content of production reflects genuine effort. To me, however, Kendrick Lamar is not a superhero simply because of his craft. It is the thought that led him to create what he did, that triumphs my heart. To sum it up in a word, Lamar’s superpower lies in this ’empathy’. He does not take his privilege for granted.

Suggested read: #BestOf2016 The Top 10 Most Viewed Songs On YouTube In 2016

We are swamped with the burden of trying to ‘be something’, to ‘make something’ of ourselves and our lives. A couple of months ago, I stumbled on this YouTube video:

It’s called ‘The Race of Life (white privilege)’. The video records a coach speaking to a large group of young adults, all standing in line. The winner of the race gets $100, but there are interesting conditions levied on the same. The coach will state a couple of scenarios in front of the group. If it applies to you, then you take two steps forward. Otherwise, you stay wherever you are. The circumstances he outlined were: “Take two steps forward if both of your parents are still married”, “Take two steps forward if you had access to private education”, et cetera. Once he was done, he asked everybody to look at the people behind them, to see what ‘privilege’ means. The concept of ‘white privilege’ is heavily debated, but a crucial part of our collective social struggle. It was not surprising that the ones with ‘colored’ skin, were generally behind everybody else. They formed the last and second last line, for the most part. Kendrick Lamar songs bring this reality to the forefront, right under the noses of people who have gotten too comfortable in their entitled existence.

Lamar is an authority on the very privilege he works around. Despite being an American, despite the celebrity-cred, and the relative security that comes with a Green Card, Lamar is the epitome of empathy. He not only draws power from his own struggle, but also recognizes his own privilege, and labors to build a discourse for the Voiceless. His brilliance lies in his endless effort to build a collective anthem that embodies the perpetual conflict in a ‘colored’ person’s endeavor to exist within the majority- or, to exist at all.

‘DAMN.’ (2017) and An Anthem In The Making

“My biggest vice is being addicted to the chase of what I’m doing. It turns into a vice when I shut off people that actually care for me, because I’m so indulged spreading this word. Being on that stage, knowing that you’re changing people’s lives, that’s a high. Sometimes, when you’re pressing so much to get something across to a stranger, you forget people that are closer to you. That’s a vice.”

–Kendrick Lamar, in an interview for ‘RollingStone’

This is the album that won him a Pulitzer. The most popular track ‘HUMBLE’, garnering nearly 500 million views, was Kendrick’s first song that hit no.1 on the Billboard Hot 100. It seeks to decry stereotypes (“If I kill a nigga, it won’t be the alcohol”); reclaims language, taking colonial slur and using it to empower one’s self. The track speaks of checking your privilege; of being aware of your gains but not boastful of them.

Suggested read: 10 New Artists Who Will Rule The Music Scene In 2017

In ‘All The Stars’ ft. SZA (from the ‘Black Panther’ album), Lamar says: “Tell me what you gon’ do to me/ Confrontation ain’t nothin’ new to me/ You can bring a bullet, bring a sword, bring a morgue/ But you can’t bring the truth to me/ Fuck you and all your expectations/ I don’t even want your congratulations/ I recognize your false confidence/ And calculated promises all in your conversation/ I hate people that feel entitled”. Kendrick Lamar songs, with their explicit lyrics, are painfully true in an era where the Ku Klutz Klan still finds Nazi-sympathizers; where the President of USA hides his misogynistic, homophobic, and racist body within the shiny interiors of an undeserved fortress; where the ‘upper-class’, the ‘privileged’, the ‘white’ still consider the concept of ‘entitlement’ as reverse-racism.

“I was a good kid in a mad city.”

In ‘DNA’, Lamar traces the age-old racist perception that the ‘black’ man’s genetic composition is flawed; that they inherit criminal tendencies from their forefathers.

The official music video depicts a police interrogation, where Lamar has been charged as guilty. The use of a ‘non-white’ entity as the Officer (played by Don Cheadle), shows how our own people can perpetuate their oppression, or how the question of personal survival forces them to change sides.

Compton, California, where Lamar was born, is notorious for its abundance of violence. In a segment of the song, he raps:

“I know murder, conviction, / burners, boosters, burglars, ballers, dead, redemption, / scholars, father’s dead with kids”. He outlines the stereotypes in: “Loyalty, got royalty inside my DNA / Cocaine quarter piece, got war and peace inside my DNA / I got power, poison, pain and joy inside my DNA / I got hustle though, ambition, flow, inside my DNA”.

Co-existing with a white population, on the edge of racism, near ‘colored’ neighbors who turned on each other, Lamar talks about the dichotomy he built his home on. The ‘war’ and ‘peace’ within him, are the ‘id’ and ‘superego’ in all of us. Psychoanalysis does not change with the color of our skin. In a trope that is only too popular in the present scenario, we know that ‘black’ criminals are thought of as “terrorists”, while white criminals are only “mentally disturbed”.

When asked about his view of the future, Lamar exclaimed that he was “optimistic”. He fills his discourse with a distinct brand of protest, of perseverance, and of triumphing the odds. “When I was 9, on cell, motel, we didn’t have nowhere to stay / At 29, I’ve done so well, hit cartwheel in my estate / And I’m gon’ shine like I’m supposed to.” (‘DNA’, 36-38)

‘Alright’ (‘To Pimp A Butterfly’, 2015) and The Ideology of A Superhero

“We saw the stones that they had to dig up day to day. That was crazy. You could feel their spirits there, basically saying, “Take a piece of the story back to your community.” That’s exactly what I did. To Pimp a Butterfly, which is me talking to my homeboys with the knowledge and the wisdom that I gained.”

-Kendrick Lamar, on visiting the African prison cell where Nelson Mandela was held

The official music video for ‘Alright’ encompasses the crux of Lamar’s consciousness. In a monologue that features exclusively in the track used for the video, Lamar says:

“But while my loved ones were fighting the continuous war back in the city, I was entering a new one / A war that was based on apartheid and discrimination“.

What Lamar created is still one of the most relevant texts on the subject of neo-colonial racism, and psychological warfare. Lamar is the omnipresent Messiah saying, “Bitch, we gon be alright“, even as we are cradled in the lap of destruction.

In the initial sequence, a car is shown with four ‘colored’ passengers. As the frame pans out, we see the car being carried on the shoulders of four white policemen in uniform. The motif of reversing the existing power structure recurs in Lamar’s work. In the end of the video, a white policeman mimics a gun with his fingers, and shoots Kendrick. The very fact that the bullet pierces his heart, and he is thrown off the post he was perched upon, shows that even the idea of hatred holds as much weight as actual weaponry. As his body hits the ground, the camera cuts to black. A second later, it records a glimpse of the scene where Lamar, lying on the floor, presumed dead, opens his eyes and smiles. “My knees gettin’ weak, and my gun might blow / But we gon’ be alright”.

Slate culture writer, Aisha Harris, speaks to Business Insider of the song’s essence as: “a kind of comfort that people of color and other oppressed communities desperately need all too often: the hope – the feeling – that despite tensions in this country growing worse and worse, in the long run, we’re all gon’ be all right“.

Suggested read: It’s High Time We End The Misogyny In Music, And Here’s Why

Kendrick Lamar songs are a genre in themselves. More than hip-hop, Lamar creates genuine ‘rally-cry’s. He is preparing for a grand party called Revolution, and we are all invited. Hip-hop, and rap, as a medium have contributed heavily towards creating an artform of protest. We need it now, more than ever. Dana Canedy, the administrator for the Pulitzer prizes, said, “The time was right.” Kendrick Lamar is the first rap artist and non-jazz/classical musician to have received the prize. This shows a widening of the horizon of acceptance, of recognition, of being heard. As Lamar said at the end of his speech at the 58th Grammy Awards, “We’re gonna live, aye.” Hip-hop is here to stay, and it is time for the African-American identity to take center-stage.

Featured image source: Instagram

![[Insta-Celeb Series] Let Selena Gomez’s Style Fashionspire You!](http://www.newlovetimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Selena-gomez-style-150x150.jpg)