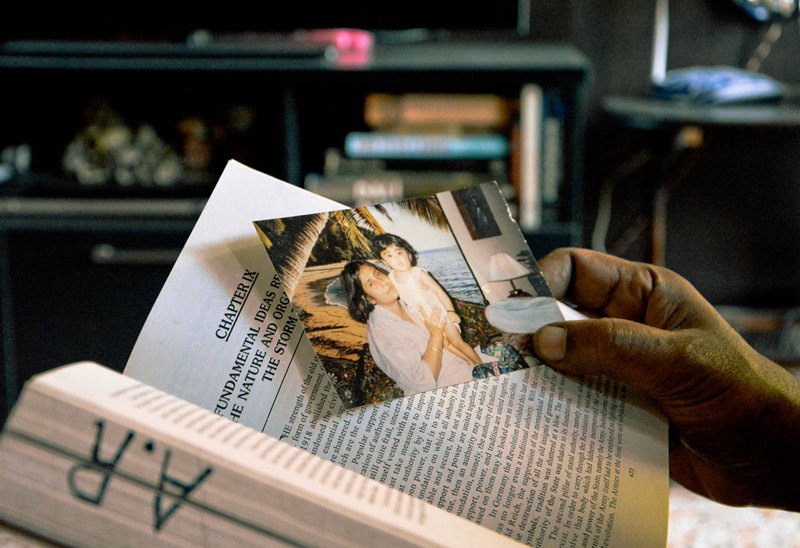

I left home when I was 17. It was June, 4 days before my Dad’s birthday. I had never missed his birthday until that time. Before leaving for the station, I kissed my Grandmother, whom I called Thamma, and looked into her eyes. When a tear fell from them, I knew something was changing.

The only times we realize what our homes mean to us is when we are leaving them. Leaving means, you have not left yet, and that makes it worse; you have a choice of staying, and yet, you don’t have a choice of not leaving.

Image source: Riya Roy

I still remember the journey to the station. Baba was driving, and mom, holding on to her prayer beads, sat beside him, mumbling prayers in a language she didn’t understand, but it was prayer all the same. Sitting in the backseat, I watched how the townscape changed from a rocky terrain to plains with lush tea gardens flanking on both the sides. The sun was about to set over the horizon; the sky was almost tangerine. The tea-tribe, after a toiling day in the garden, was marching toward home, teasing each other along the way. I watched a silhouette of a flock of birds fly homeward across a sky that had now turned a tinted pomegranate crimson, which in the blink of an eye of someone lost in thought, drained into a color that resembled the ink stains on my hands.

Suggested read: Friends Leave, But They’re Never Really Gone…

When we reached the station, Baba wanted to take a picture of me with my suitcase. I asked him to wait and ran my fingers through my hair, setting it just the way the hairdresser had done the day before; yes, we had discovered Facebook by then. As we waited for the train, we were overcome by a specter of silence. There was nothing we had to say to each other, or perhaps there was so much left unsaid all these years that we were wondering where to begin. Pacing up and down the platform, I thought about all the plans we had made and cancelled, assuming there will be time but alas! I thought about my Thamma and her food, the aroma of the spices pervading the space around me. The aloo-posto, the hinger-kochori, the sorshe-maach, the dhakai-porotha, the khejur-chatni, and even the humble bengun-bhaja brought water in my mouth and tears to my eyes.

We’ve always been so comfortable sitting in silence, doing our own thing, but today, the silence was stinging, and upsetting it became necessary. However, as soon as I started telling Baba how excited I was about college and living on my own for the first time, we heard a roar in the distance. The dark body of the train, much like a serpent, was creeping its way into the platform. The engine came to a screeching halt right in front of the Banyan tree, as promised by our coolie, who now stood beside us, all smug because of his precision. While the second’s hand concluded two revolutions, my suitcase and I were parked in our seats. I looked outside the insulated window, and saw my parents feverishly wave at me; since the windows were sealed and tainted, they were actually waving at a 70-something lady who sat opposite me all perplexed, trying to think if she knew this exuberant couple. My parents couldn’t see me anymore, so I knew this was the right time, and released the tears that I had been holding back all this while, to find a trail and trickle down my cheeks.

Image source: Arya Kishore Sarbadhikary

When I arrived at the big city, I did not feel welcomed. The people around me knew at once that I was an outsider; though the local language was my mother tongue (in my case it would be father tongue), the way I spoke it, gave away who I was. At college too, we were a herd of girls who preferred to remain cocooned as though we were under a serious threat from the girls who belonged there. The break time was the worst, and the lady at the canteen made sure of that. I remember, one rainy afternoon, I walked into her crammed canteen and asked for a coke. She cleaned a bottle, opened it, and enthusiastically, asked me to gobble it down quick. This woman who had never even smiled back at me all these 67 days of my existence in this city, was suddenly all animated… hmmm I could sense something fishy. As soon as I took a sip, she breathed a sigh of relief, and I knew why. I searched the body of the bottle to look for the expiry date and there it was! I shoved it in front of her face and glared at her. Instead of being sorry about the whole thing, she snatched the bottle from me, and said, “But you have to pay!” In that moment, I knew how the rest of my days in this bizarre cosmopolitan jungle would be like!

The bus rides to college weren’t my favorite either. Jumping into one that’s in motion, would add another impetus, to an already endless list, to bunk classes. And even if you manage to get up on one, maneuvering your way out of a swarming bus, is a task worse than the ones on Blue Whale! While I stood near the steps of the bus watching my stop disappear in the background, I would plead the conductor to bring the demon to a halt. He would signal the driver with a “aste ladies” (slow down, a lady is getting down), during which I would have to hold my breath to tuck my tummy in, so that he wouldn’t nonchalantly go ahead and add to his cautionary, “petey bachcha ache” (she has a baby bump)!

These rides brought out the worst in me. I compared the people here and back home; I thought of the rough hands the people of my hometown so proudly exhibit as a sign of hard work and confidence. I wondered how the coarseness of the terrain and people’s appearance had melted away with the miles, and had settled into the hearts of the people of the city, that is if there was a heart beating somewhere in there! It reminded me of a bangla song my father used to hum…

sono bondhu sono,

pranheen ei shohorer kotha,

iter panjore,

lohar khachay daroon marmo batha

Loosely translated it would be:

Listen my friend.

Listen to this lifeless city’s legend.

In cages of bricks, in prisons of steel, there exist terrible torments

Suggested read: Dark And Lovely: My Experience Of Growing Up As A Dark-Skinned Indian Girl

The city resented me and I responded likewise. In the months to come, I would make a calendar for myself, crossing out dates with red, marking each day that I was surviving the city. The cross also gave me strength in that it was a symbol of how the city was failing to get to me. All this was strange because the city which harbored me now, was home to my father and our forefathers, and thus in a way this was supposed to be my city too. And stranger still, the land that I call home, which I had left behind, was my birthplace and where I fitted well, but to think of it now, I never belonged there either.

Image source: Riya Roy

Every single day, I would think of home. I would picture my dad waking up to the best brew, the secret of which my mum is yet to share with us. I would imagine my dad sitting down for breakfast; nibbling on a piece of bread and complaining about how his poached egg is not done the way he wants it, but that little detail of how he wants it to be, is invariably omitted every single time! Dad would then ask mum to bring her bowl of oatmeal and eat with him, which she would give a pass, because she still had to finish her yoga routine. At lunchtime, while I was grabbing a quick bite at the nearest CCD, I would think of my parents sitting down for lunch, devoting a slice of their time and attention to the meal; looking at the empty dining chair and talking about me, maybe? I hoped they did.

Amidst the monotonous crowing of the crows, afternoons would fade into evenings. I knew back home, the family was sitting in a room together doing their own thing, until Baba poured some ginger ale and softened the lights. The ginger ale ritual had started a year ago when my Thamma’s health started failing. We would all watch as she would empty her glass in one go, and turn a shade of crimson, as though someone had pinched her cheeks; she looked beautiful.

As months went by, it was easier for me to answer where I was from, but when people asked where is home, I would need to pause and think, and think again… the pause grew longer with each year that I was away.

Though my rift with the people continued, I found solace in the city through her food, the festivities, and the buildings with gothic and Victorian architecture. On days that I paid more attention to the city around me and less to my landlady or the grueling weather that just got worse with each passing month, I marveled at the history that the city carried in the folds of her sarees, in the khair that adorned her paans, and in the labyrinth of her narrow lanes and by-lanes. With her roddur makha baranda (sun-soaked verandas), laal-itther bari (red brick houses) and shobuj jannla (green-painted windows), the sorceress had me spellbound.

Image source: Arya Kishore Sarbadhikary

In this city, breathed my father’s childhood and his youth. All the stories that I’d been told through these years, and etched in my mind like a kaleidoscope, had happened here. This city had kept it all safe for me to come and explore and add to the memories. Walking on her pavements, I would feel that Baba must have walked through the same gullies; he must have mulled over the same thoughts that I dwelled on as an 18-year-old; he must have been troubled by the same confusions, been happy because of the same beginnings. The city served a connection between me and my people back home.

This city was also where my grandparents got married. Though theirs was an arranged marriage, and the would-be couple wasn’t supposed to see each other until the wedding day, my Dadu apparently confessed to my Thamma later, that he and his friend, a week prior to the wedding, had perambulated around her building in the tormenting afternoon sun, hoping to catch a glimpse of her. As I stood outside that very building, a woman who lived there now, walked out into the balcony with her evening tea and newspaper, and turned on the radio. To the fleeting tune of “Purano sei diner kotha bhulbi ki re hai…”, (How will you ever let go of the memories of the good ol’ days), I walked away.

Pujo was round the corner. Autumn had arrived, and there was a nip in the air. The fragrance of burning incense sticks and floral offerings had taken over my senses; I breathed in the warm aroma from sweets being cooked day in and day out under tents that permeated every nook and corner of a city starved for space.

Image source: Arya Kishore Sarbadhikary

The other 360 days of the year, for the city and its people, is a preparation time for these 5 days of Durga puja. Every corner is scrubbed, scoured, and illuminated. One will find a conglomerate of artisans from all over the state converging in the city to extend their expertise in bringing to life the imagination of ‘Ma,’ the mother of all gods by covering the skeletons made of bamboo with straw and clay, cloth and canvas, to bring joyous trance and obedience in the lesser mortals. Once the deity arrives, the city can expect to go sleepless.

Walking down frequent roads, you will stumble upon lanes that you never noticed before, but hold a niche in the city’s history. By the same token, the people during these few days, drop their guards, and let you get a glimpse of who they really are. They aren’t the cranky auto-rickshawala who screams at you in the morning for “khuchro” (coins); they aren’t the irate bank lady who gives you a dirty look when you miss slipping in your check through the window in the first attempt; they aren’t the lewd 60-year-old man who touches you inappropriately in the metro because he is sure you won’t suspect him, or more importantly, call him out; they aren’t the relative who takes you to a boutique restaurant and makes you order so that when you aren’t able to pronounce the fancy names, their sickening sense of humor is mollified.

So who are these people who dwell in this city? Here’s what I realized: These are people who drop everything they are doing to guide you home when you are lost for the hundredth time; these are your friends’ moms who invite you over and cook you your favorite meal, guessing rightly that you are homesick; these are people who sit in ‘paras’ and invite you into their addas (conversations) regardless of where you are from. And what addas! From nuclear physics to conspiracy theories; from politics to providence, from Picasso and Michelangelo to Ramkinkar Baij and Jamini Roy; from Shaw to Tagore; from Bertolucci to Ray; from Hitler to Gandhi and Mao; from Messi to Ronaldo; from Bradman to Sachin; and finally, to how Nadal will never be the next Federer. At the end of the day, one understands why and how this city pioneered the Indian Renaissance.

Enamored of the city and its people, one day, when I returned to my little room after a crazy session of pandal-hopping, I felt something unusual; I felt a sense of belonging. That afternoon, when I walked into my room, I could feel my truest self, the self that I do not reveal unless I know I am in a safe harbor. I felt I can now drop “the act”. As I switched on the bedside lamp, the light poured into the room slowly and quenched the darkness around. The flowers on the makeshift dressing table smiled at me like every day, but this time, I smiled back at them. I touched the velvety folds of my linens and in their delicateness, felt being received. For the first time in a long time, I felt I had returned home.

Suggested read: How It Is For Someone Living With Anxiety: My Story

The fact that one day the new city would feel familiar and something like home, was a detail I knew, but was never ready to admit, as if saying it out loud would actually make it happen! What I did not anticipate, however, was what would happen when I return to the place I was from? During my first summer break back home, things looked the same on the surface: the house, the people, the hills, the parks and its benches, the neon street lights, the river and its banks, every single thing. Something however, had changed, fundamentally: something I didn’t know, something I didn’t want to know.

Image source: Riya Roy

There are so many people like me out there, who left home, typically to return at some point. It was only later that they realize that anywhere can be home. I am not offering an epiphany here. Though this idea, that you carry your home wherever you go, is liberating; it is also scary. It essentially means that home is not to be found anywhere in particular. It bears out that home is not where we are from, and home is not where we are at the moment. So, how can one assure oneself that home exists somewhere in the future? That someday, you will be able to point at a place and call it home?

Featured image source: Riya Roy