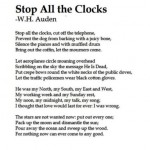

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

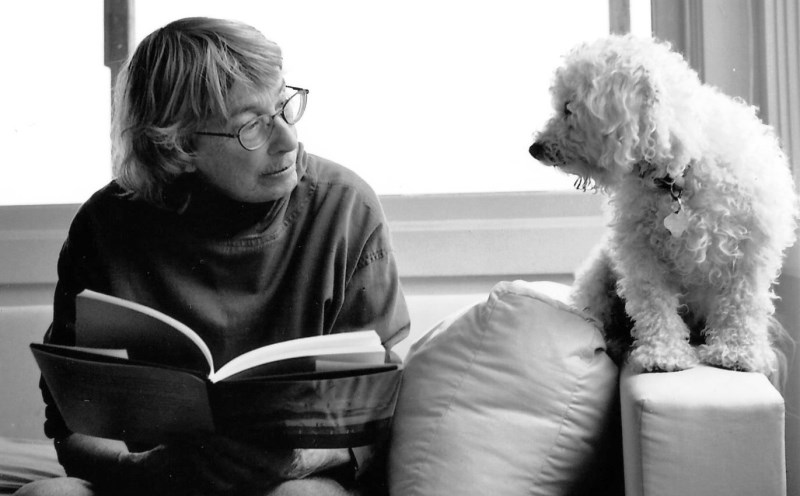

Few poets have been able to master the art of paying attention the way Mary Oliver had. One of America’s most popular and beloved poets, much of Oliver’s poetry deals with this quality of hers which she had been honing since her childhood in the rural part of Ohio, to escape her dysfunctional family. Having an abusive father and a neglectful mother, Oliver took refuge in the company of dead poets and amidst the bounty of Nature. These “two great passions” of Oliver remained with her till the end of her life. Much of Oliver’s poetry deals with her subtle interactions and experiences with different elements of the natural world, in this regard she was greatly inspired by the Lake Poets of the Romantic Era, namely Keats and Shelley. She believed Walt Whitman was a brother she never had, and always carried a copy of his poems in her knapsack as she went on her long walks in the woods.

Suggested read: “Beyond Speech, Beyond Song, Only Not Beyond Love” The Poetry Of Eavan Boland

Oliver passed away on Thursday at the age of 83 at her home in Hobe Sound due to lymphoma, as confirmed by Bill Reichblum, her literary executor. She was one of America’s most popular and beloved poets; loved in equal measure by fans like Oscar-winner Gwyneth Paltrow, and former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. With over 15 collections of poetry and essays to her credit, Oliver boasts of a rich and fulfilling poetic career, having won both the Pulitzer Prize (in 1984 for her fifth collection of poetry titled American Primitive) and the National Book Award (in 1992 for New and Selected Poems). She had started writing poetry from the tender age of 13, but was published at the age of 28 in 1963. Her first collection of poems was called No Voyage and Other Poems.

Oliver said, “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work.” That is exactly how she found inspiration for most of her poetry- Mother Nature was her greatest muse. The subjects of Oliver’s poetry- nature, beauty, and God- were often subject to ridicule by most literary critics who could never take Oliver or her poetry seriously. While discussing her poetry, critic David Orr said, “One can only say that no animals appeared to have been harmed in the making of it.” But Oliver was never one to be deterred by such remarks. Her beliefs and her perception of poetry remained unchanged throughout her life. Perhaps that is what makes her such a wonderful poet.

Oliver firmly believed that poetry had no purpose being “fancy” or sophisticated; it was meant to be straightforward, honest, and always to the point. Ruth Franklin, in a New Yorker article about Oliver’s 2017 book Devotions, said that the reason Oliver is so popular among the masses (both in America and elsewhere), is due to the accessibility and simplicity of her writing. One need not be an academician or an intellectual to truly understand the meaning behind her poetry. Reading Oliver’s poetry feels like you’re directly being spoken to by the poet; all her words are meant for you. In a 2012 interview with NPR Radio, she said- “Poetry, to be understood, must be clear… It mustn’t be fancy. I have a feeling that a lot of poets writing now, they sort of tap dance through it. I always feel that whatever isn’t necessary should not be in the poem.”

Throughout the 30 years of Oliver’s career as a poet, we find her grappling with questions pertaining to the meanings of life, death, the relentlessness of time, and the brevity of beauty and human existence. Her spirituality was deeply rooted in nature, and she believed that it is only by attuning oneself with nature that one can truly understand the divine. Although Oliver’s poems tend to often come with a moral lesson, and have the tonality of a prayer, she was utterly disdainful of organized religion; but found God reflected in her surroundings. Oliver’s poems were not meditations on eternal life; rather they were a memento mori, a meditation on death.

When death comes

like the hungry bear in autumn;

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

to buy me, and snaps the purse shut;

when death comes

like the measle-pox;

when death comes

like an iceberg between the shoulder blades

I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering:

what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?

In these opening lines from her poem “When Death Comes”, Oliver invites readers to ponder upon that final, irrevocable moment of death in all its starkness and honesty. On the one hand, she reflects how death cannot be avoided, it arrives like a “hungry bear in autumn” with the finality of a purse snapping shut. However, she also harbors a sense of hope, that even in the face of such inescapable darkness she will retain her curiosity and interest about the Great Beyond. She is painfully aware of life’s transient nature, but that does not deter her spirit. Instead, this awareness pushes her forward to embrace each day as a treasure; to cherish life despite its common and singular nature. This is the only spiritual awareness that matters to her, as Douglas Burton- Christie noted in the essay “Nature, Spirit and Imagination In The Poetry of Mary Oliver.”

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Suggested read: Dear Writer, Suicide Is Not Poetry

Her poem Wild Geese, opening with these lines, is an attempt to answer a question that seems to drive all of Oliver’s poetry- How are we to live? Oliver was always looking for the most fulfilling way to live life, to experience it in all its shades and hues, to live truthfully to oneself, and to cherish one’s surroundings. Religion teaches us repentance and punishment is the only way to earn God’s graces, and to rid ourselves of the sin that taints our souls by virtue of birth; it teaches us to be ashamed of our “animal instincts” and to repress them right from our formative years. Oliver, while deeply spiritual, subverts these teachings of institutionalized religion and tells us that the only way to lead a worthwhile life is to let the inner animal in us take over. Grief, she says, is an integral part of our lives. But the world goes on, and our grief constitutes only a miniscule part of it. No matter how lonely we might think we are, each one of us has a proper place in this universe, we are all members in “the family of things”. It is in her painful self awareness that Oliver finds her solace, and offers the same to her readers.

“When it’s over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.”

Oliver is matchless in her undying zest for life. Her greatest fear perhaps was to live a life in which she wasn’t filled with amazement at her surroundings, a life crumbling under the weight of facts; she did not want to end up “simply having visited this world.” Her yearning to live a good life is what resonates with readers even today, as we scramble about trying our best to comprehend the world we live in. However, Oliver was also a great writer of love poetry, all of them addressed to her partner Molly Malone Cook, a photographer she met in the late 1950s, and with whom she spent all her life until 2005 when Cook passed away. Oliver’s love poems have not garnered the critical acclaim they deserve but a single reading will bring to light the tenderness and passion each line gently cradles. It is perhaps best represented in her prose- poem “The Whistler” in which Oliver realizes that despite spending years with her lover, there are still parts of her that remain unknown to the poet-

“I know her so well, I think. I thought. Elbow and ankle.

Mood and desire. Anguish and frolic. Anger too.

And the devotions. And for all that, do we even begin

to know each other? Who is this I’ve been living with

for thirty years?

This clear, dark, lovely whistler?”

Suggested read: Odes That Will Fill You With Love For Poetry

Mary Oliver may not be around anymore to remind us to keep some room in our heart “for the unimaginable”, but her simple, yet poignant words will continue to inspire amazement, to teach us that sometimes a “box full of darkness” is the greatest gift, and to remind us to never hesitate in that “sudden seizure of happiness”. The world will remember her the way she would have wanted it to- the bride married to amazement, who took the world into her arms, who loved every mortal thing but let go when the time came, and strode head-on towards Death, that cottage of darkness, with the ardent hope that-

“Maybe death

isn’t darkness, after all,

but so much light,

wrapping itself around us–”

Featured image source: Instagram